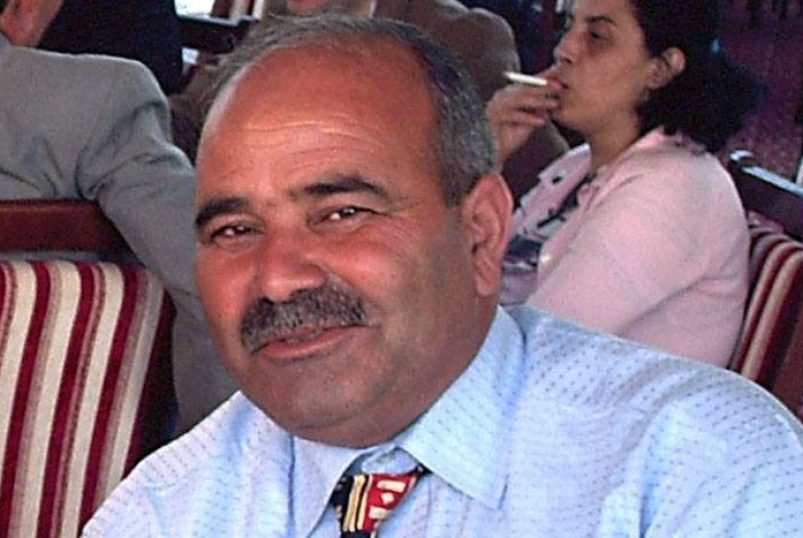

I am Sarah, the eldest daughter of Abdullah Al-Khalil; my father was born on 2/1/ 1961 in Al-Raqqa. My father studied law at the University of Aleppo and graduated from it in 1986. Just after his graduation, he worked in the office of a lawyer and then opened his own office. In addition to his legal work, he also worked as a volunteer for a human rights association in defense of prisoners of conscience and political detainees, in particular the detainees of Tadmur Prison.

As a result of his work and his position against the Assad regime, which was carried out in secret. He was being summoned by the intelligence for investigation every now and then because of suspicion or because of the reports of security informants. However, since the beginning of 2007, the year that my father nominated himself for the position of the Syrian presidency, all his everyday movements and even our lives became as a family became under surveillance, in particular after he was summoned by the Military Security in the city of Deir Ezzor, just after that incident of his candidacy, which made him known perhaps not only in Raqqa but to most Syrians for his forbidden act in Syria.

For everyone, Abdullah Al-Khalil is Lawyer Abdullah Al-Khalil, but for me, he is my father. Our relationship with him, as his five sons, was special; he was present in all the details of our lives. We found him easier to deal with, and he was more generous with us than our mother. He was always there to help us with our homework and answer our many childish questions. He always played with us. We always accompanied him to the farm we owned on the outskirts of Raqqa city. He insisted on taking care of the olive trees by himself. My brothers and I were so attached to him that we sometimes accompanied him to his workplace.

The year 2011 was a turning point in our family’s life. My father was one of the regular participants in the peaceful demonstrations and one of the organizers of the peaceful movement against the Assad regime. We also accompanied him in most of those demonstrations, for we used to share everything with him. He was arrested five times and imprisoned for periods ranging from forty to four days. For months, in the prison, they were putting various pressures on him, and he always came back in a deteriorating health condition. The regime even demolished our farm under the pretext that there were weapons in it.

In 2012, my father had to leave Raqqa to avoid a long arrest this time, and later in the same year, my mother and I left secretly to join him in Turkey. In Turkey, my father worked with Urfa State to deliver relief aid to the liberated Syrian area. He returned to Raqqa on 3/11/2013 immediately after its liberation, being the head of the local council of the province while we remained in Turkey. He visited us after going there three times before he was kidnapped while returning from his office in Raqqa to his brother’s house located on the outskirts of the city.

That night, we were in contact with him before he left the office, and the next morning we were told that a group of masked men had intercepted him in the street and took him. At that time, kidnapping and ransom demand was common in Raqqa, so we thought at first that the matter would not take so long, but actually it took so long and nobody called to ask for anything. My father’s family asked both the Free Army and Ahrar al-Sham that controlled Raqqa at that time about him, but they did not get any information about him or even about the kidnapper.

With ISIS taking control of Raqqa later and seizing his office and house, we became sure that ISIS was behind that kidnapping. After ISIS took over the house, my mother returned to Raqqa in order to regain the house. She tried to

ask ISIS members who were in the house about the fate of my father, as they entered the house without removing the door and with the same key of which she owned a copy in her bag, and only my father owned another copy of it, for my mother noticed that the key was on the counter of the door. Those members told her to wait for the prince to ask him about my father, but she waited for a long time in vain. Therefore, she returned to Turkey.

After Raqqa was out of ISIS control, we tried to communicate with SDF through my father’s acquaintances and through the Syrian coalition. Whenever we saw news on the communication sites about finding detainees, we pursued the sources and tried to find out any information that assures us of his fate, whether he was alive or dead, but all the parties did not help us. I would like to say that my father’s absence made us grow up before our time, for we assumed a responsibility that we were not accustomed to in his presence. We had to bear his mysterious absence, which never allows sadness to take its normal course so that our souls reside. It is true that we live and grow and continue our studies, but we are always stuck in the moment of my father’s disappearance.

Sarah Al-Khalil